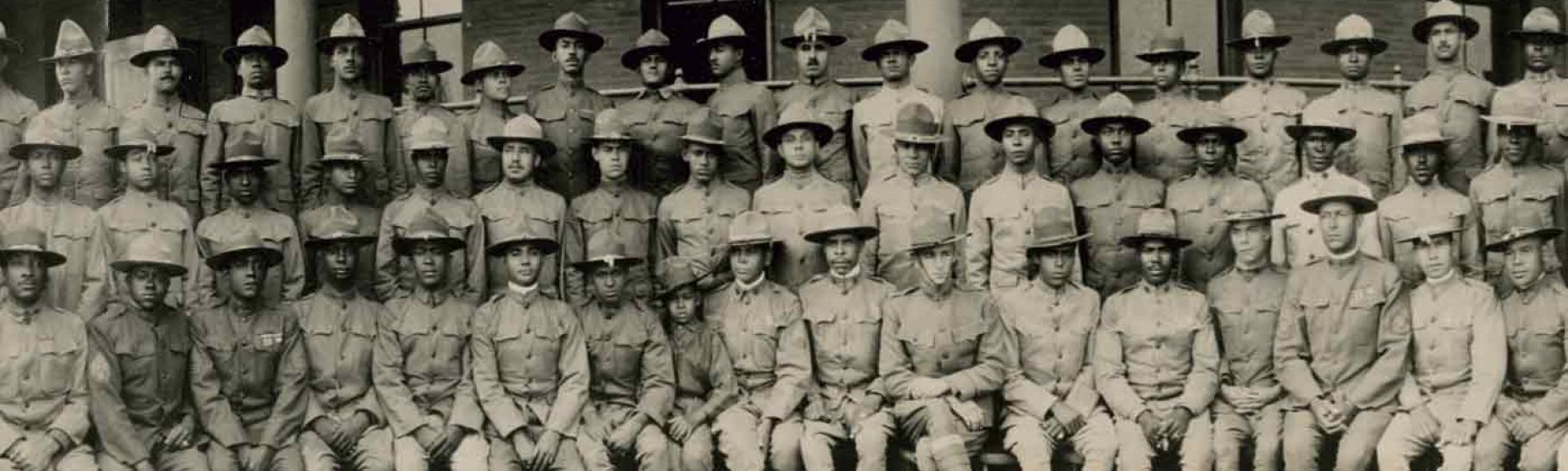

Black Officers at Fort Des Moines in World War I

“With less than thirty days notice the superb youth, the very best brain, vigor, and manhood of the Race gave up comfort, position, future promise and outlook, in their various civil locations, and from the North, South, East and West, started on their voluntary march to Fort Des Moines in answer to the call…

God grant that their efforts and sacrifices may open a brighter and better day for all downtrodden people of the earth and especially the oppressed colored people of these United States.”

-George H. Woodson, 1917

Co-founder Niagara Movement 1905 and National Bar Association 1925

As the United States entered World War I in 1917, thousands of black Americans—from the North and South—enlisted with the hope of fighting Germany in the “War To End All Wars.”

Isolated in Iowa

Despite the eagerness demonstrated by blacks to join the fight, black enlistments were limited by the federal government. At the same time, political pressure from a number of black organizations including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) pushed for black officer training. Government officials feared the race issue would harm the war effort. A compromise was reached by allowing one officer candidate school to open to black college graduates. The announcement was made that 1,000 black officers would be trained.

All-black Howard University in Washington, D.C., wanted to host the camp. But government officials believed the black cadets would fail. They feared the media in the eastern United States would rush to cover the story about the military's “embarrassment.” They wanted an isolated location far away from the east coast media. They found the perfect location in an abandoned cavalry post in Iowa.

Fort Des Moines, Iowa, had been built in 1901 on 400 acres. It opened in 1903 with the arrival of the all-black 25th Infantry prisoner guard. The 11th Cavalry arrived in 1904. The 2nd Cavalry came in 1907, and the 6th Cavalry arrived in 1910. But the horse soldiers (cavalry) had left in 1916 for duty along the Mexican border, so the facilities were available.

The Cadets Begin Training

In May 1917 the first black officer candidates arrived at Fort Des Moines. There were 1,000 black college graduates and faculty from Howard, Tuskegee, Harvard and Yale universities. Two hundred fifty non-commissioned officers (sergeants) from the army’s four black standing units—the 9th and 10th Cavalry “Buffalo Soldiers” and the 24th and 25th Infantry—would also attend the camp. (The term Buffalo Soldiers was used to identify all-black military units that were formed after the Civil War in 1866.) The 1,250 candidates made up the 17th Provisional Training Regiment.

Des Moines’ 5,000 black residents were astounded at the highly educated black cadets. The white community was, for the most part, receptive. The white merchants were especially friendly to the black cadets who were paid $75 in gold coin.

When it came time to assign a commander for the black soldiers, Leutenent Colonel. Charles C. Ballou was awarded the job. Ballou had political connections that probably helped him get the position. He was also white. Many people thought a black officer, Colonel Charles Young, should have been given the post. He was a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and had made a name for himself as a Buffalo Soldier. But Young was forcibly retired by the army for “high blood pressure.” Young later rode his horse all the way to Washington, D.C., to prove he was fit to serve. But his experience and remarkable service record were overlooked.

After race riots at Camp MacArthur, Texas, and East St. Louis, Illinois, and fearing white community reaction in Des Moines, Ballou organized a “White Sparrow Patriotic Ceremony” at Drake University stadium in July 1917. At the event the black cadets marched and sang Negro spirituals for a crowd of 10,000 spectators.

Leaders Among the Cadets

A number of important national and local leaders were among the cadet class, including Elder Watson Diggs who had co-founded Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity in 1911. Frank Coleman and Edgar Love had done the same with Omega Psi Phi Fraternity the same year. Cadet lawyers Samuel Joe Brown, Charles Howard and James Morris would go on to co-found the National Bar Association in 1925.

After 90 days of rigorous technical and physical training, 638 captains and lieutenants received their commissions on October 15th and were dispatched for basic training at a variety of camps including Camp Dodge.

The all-black Alabama enlisted regiment at Camp Dodge across town received a different welcome from the Des Moines community. Paid in government script and often illiterate, they regularly faced discrimination.

To France to Fight

In June 1918 the Fort Des Moines officers reunited at Hoboken, New Jersey, for transportation to France and combat against Germany. They were the 3rd Battalion, 92nd Division of the American Expeditionary Force. They would fight bravely across France and in the bloody Meuse-Argonne sector.

The final battle of World War I was at the historic French city of Metz where the Germans had built a great fortress. For the first time in U.S. military history, a black regiment under the command of black officers from Fort Des Moines led the attack in a major battle. Flanked by the American 56th Regiment and the French 8th Army, the 92nd fought to within 800 yards of the German fortress when the bugle was blown announcing the war’s end.

In 1919 the returning Fort Des Moines officers were greeted by racial violence that flared across the nation. In spite of the racism and violence, they flourished and set the stage for a changing nation. The black officers of Fort Des Moines demonstrated their ability to perform and opened the door for all who came afterwards including legendary officers General “Chappie” James and General Colin Powell.

Famous black Iowans who graduated the Fort Des Moines camp and survived combat in France included noted journalists, civil rights activists and lawyers Charles Howard and James B. Morris, who would publish the Iowa Bystander newspaper from 1922-1972. James Wardlaw Mitchell’s Community Pharmacy anchored the historic Center Street business district in Des Moines for many years.

In 1997 the grandson of Cadet James Morris founded a memorial park honoring the WWI camp. Robert V. Morris created a 4.6 acre museum and grounds called the Fort Des Moines Memorial Park.

Sources:

- Robert V. Morris, Tradition and Valor. Journal of the West, (August 1999).

- Scott, Emmitt. Scott's Official History of the Negro in the First World War, 1919.

- Thompson, John Lay. History and Views of Colored Officers Training Camp: 1917 at Fort Des Moines, Iowa. Iowa City, Iowa: State Historical Society of Iowa, 1917.

- Silag, Bill, Ed. Outside In: African-American History in Iowa, 1838-2000. Des Moines, Iowa: State Historical Society of Iowa, 2001.

Pathways

Muhammed Ali described J.B. Morris as 'a truly great man.' Morris graduated as a second lieutenant in the first black-officer class at Fort Des Moines in 1917 with other great officers.

Media Artifacts

Investigation Tip:

How did the individuals in this article affect history? Look for specific results from their actions and decisions.